2019

Exégesis sobre mi participación en el MAM Chiloé 2019

ES

Entre el 1 y 30 de septiembre 2019 estuve en residencia en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Chiloé (MAM Chiloé) tras haber sido beneficiado por el Premio Ca.Sa. 2019 de la Fundación Ca.Sa. Junto con esta experiencia, el premio incluyó ser parte de la 11ª Exposición Regional del MAM Chiloé del 12 de octubre al 12 de diciembre de 2019.

Nunca antes había estado en Chiloé, por ello, desde el primer momento que supe que me había ganado el premio, me vi muy entusiasmado por conocer Castro y sus alrededores. A modo general, fue una oportunidad increíble para reflexionar y hacer arte en un entorno bellísimo, con exuberante flora, asombrosas aves y un invaluable patrimonio arquitectónico. No obstante, conforme fue avanzando el tiempo, se me fueron revelando los diferentes y complejos pliegues de su cultura tradicional, memorias y, especialmente, sus relatos de exclusión, así como de explotación urbana y rural.

En medio de vientos fríos y de lluvias intermitentes, diría que la residencia del MAM Chiloé fue pura calidez, un ambiente de contención y protección creativa, que despertó y cautivó todos mis sentidos. Este cuenta con un equipo humano que, en todo momento, me brindó la ayuda y confianza que necesité. Sus más de 30 años de historia han forjado un robusto y consolidado espacio para la producción artística. Dada la ubicación de la residencia, relativamente alejada del centro de Castro, en las alturas del Parque Municipal, la experiencia en el MAM Chiloé fue muy parecida a lo que podría haber sido un retiro espiritual, alejado de todos los estruendos y bullicios de la vida urbana, lo que posibilitó el desarrollo de profundos procesos de introspección reflexiva. Una calma tal, que nada hacía presagiar la revolución que pronto estallaría en nuestro país.

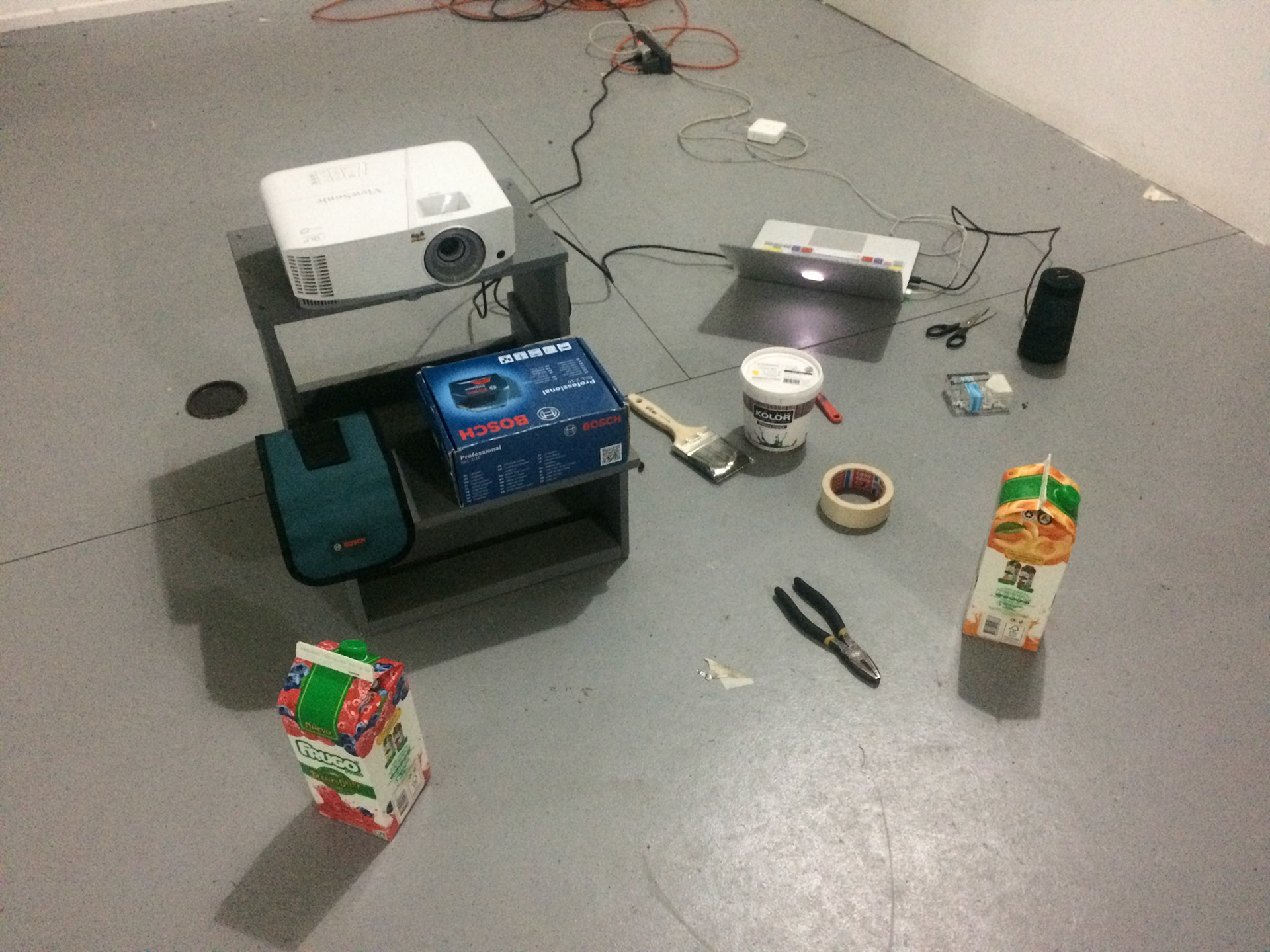

Como primer acercamiento a la residencia, pensé en una metodología de trabajo de carácter exploratoria, más que en un proyecto específico al que rendir cuentas. Contar con una metodología, medianamente clara, me permitió ordenar todo y trabajar con mayor libertad. Como primera instancia, me puse como pie forzado no traer a la residencia ningún material artístico proveniente de mi caja de herramientas; quería que lo que fuera saliendo tuviera que ver necesariamente con el lugar. Esto me instó a estar más despierto a nuevas posibilidades; diversificar mis estrategias artísticas; poner al límite mi creatividad; y valorar el principio de economía en que nada se pierde y todo se transforma en ventaja para lo que pueda construirse como obra. Como exploración investigativa, busqué recorrer el territorio, haciéndole caso, primero, a sus calles, pasajes y senderos; luego, saltando cercos y subiendo cuestas interminables, descubriendo las reminiscencias de los paisajes selváticos descritos en las bitácoras de Darwin. De igual modo, visité los principales centros culturales de Castro y sus alrededores, a fin de ver cómo se arman y administran sus representaciones locales. Asimismo, revisé la literatura general que da cuenta de los imaginarios de Chiloé y, por último, sin ser por ello menos importante, me armé un mapa mental con los diferentes lugares de venta de materiales de la más variada índole. Con esta estructura básica, comencé a recolectar los diferentes elementos materiales y simbólicos que definirían mi trabajo artístico.

Lo primero que hice al llegar a la residencia fue correr por sus alrededores, para sopesar sus pronunciadas cuestas y, a ratos, hostiles temperaturas. Alcancé a recorrer más de quince kilómetros a la redonda. El espectáculo que se me presentó fue simplemente maravilloso. Aun cuando no haya dedicado mucho tiempo de mi residencia a conocer sus diversos y populares rincones, pude visitar localidades increíbles como Lemuy, Chonchi y Queilen. Está claro que necesito volver, más aún, cuando todos me han mencionado que cada año el paisaje cambia abruptamente: derrumbes de casas patrimoniales, expansión acelerada de las zonas urbanas, devastación de bosques nativos, limitaciones en la pesca artesanal, y falta de fiscalización en torno al cuidado del medioambiente en general. Con todo lo anterior, la influencia del territorio fue un rasgo fundamental en mi trabajo; de ahí la motivación por abordar sus imaginarios telúricos y tectónicos.

Dentro de las muchas y variadas historias que guarda la isla, me concentré en el modo en que fue azotada por el terremoto del 22 de mayo de 1960, uno de los más grandes registrados por la historia de la humanidad. Según el profesor Rodolfo Urbina Burgos, historiador especialista en temas chilotes, el terremoto de 1960:

“…dejó unas 500 familias castañas sin hogar, ya por estar sus casas inhabitables debido a los destrozos sufridos, ya por inclinadas a causa del desnivel del terreno, especialmente en las laderas que fue donde más se movió, ya por anegadas como en todo el cordón palafito, ya enteramente destruidas por el terremoto y los incendios, como en calles Blanco y Thompson” (1996, p.40).

Si bien este evento sísmico ha sido mundialmente conocido como el terremoto de Valdivia, menos sabido es que Chiloé sufrió tantas desventuras y penurias como el mismo Valdivia. Aparte del movimiento de tierra y posterior tsunami, en Chiloé sobrevinieron inmensos incendios con gran poder destructivo. Explica Urbina que:

“En Castro la marea fue subiendo rápido, pero suavemente, como si se estuviera llenando un estanque. Sumergidos quedaron todos los sectores de orilla: Pedro Montt, Aguirre Cerda, Barrio Gamboa y calle Lillo. Muchas de las casas costaneras desprendidas de sus pilotes navegaban por la bahía al capricho de las corrientes. El mar se llevó unas cincuenta casas, dice el geógrafo Pedro Cunill. Parecidas escenas de casas flotantes se veían en Ancud” (2013, p.220).

Asimismo, dado el gran movimiento:

“Al interior de las casas nada se pudo mantener en pie. Cayeron muebles, estanterías, roperos, trinches; la loza y los vidrios se hicieron triza; se desplazaron los artefactos pesados, mesas y camas, y cayeron o se desencajaron las escaleras. Todo quedó volcado, confundido o destruido. Se voltearon las cocinas a leña y los braseros encendidos a la hora de la sobremesa, como era la costumbre en domingo de invierno cuando se reunía la familia en torno al fuego. Entonces se originaron los incendios. Éstos comenzaron a brotar en calle Thompson, arriba, y en Irarrázaval, abajo, para prepararse a Blanco que fue cogida por el fuego desde ambos extremos” (2013, p.218).

Ahora bien, para conocer de primera fuente las memorias en torno a este suceso y sus consecuencias en los imaginarios locales fue importante no sólo consultar su literatura oficial, sino también escuchar directamente las historias de quienes padecieron el terremoto y que aun viven para contarlo. Para ello, hice un llamado abierto con el objetivo de conocer estas historias, esto en colaboración con el Centro de Creación de Castro (CECREA). El llamado versaba de la siguiente forma:

“¿Sabes de alguien que haya vivido el terremoto del 22 de mayo 1960 aquí en Chiloé? Invítale a compartir su historia en el CECREA de Castro el día jueves 26 de septiembre. Juntos construiremos un repositorio emotivo de la memoria telúrica de la isla. Si tu historia viene acompañada de fotografías y/o recortes de prensa, estos podrán ser digitalizados y compartidos posteriormente”.

Si bien pude hacer la actividad de recolección, por escasez de tiempo no pude sistematizar la información recolectada. Sin embargo, de un modo u otro, todos los relatos daban cuenta de una angustia existencial profunda, en que la resignación y el abandono colmaban las visiones del drama. Por ejemplo, Patricia Gerding Knopke, directora de la Escuela Luis Segovia Ross, encontró entre las cosas de su recientemente fallecida madre, Laura Knopke Rutherford, un manuscrito que daba cuenta del desastre de la siguiente forma: “Al empezar a subir la cuesta Baquedano encontré a mi marido, que después de que apagaron los incendios oyeron que el mar venía subiendo y pensó igual que yo, que la familia debía estar unida y quizás morir todos juntos”. Aun cuando, por asuntos de tiempo y prudencia reflexiva, no pude dar cuenta de este tipo de narrativas en la exposición, quise que las imágenes pudiesen expresar algo de este tipo de historias.

Según el profesor Urbina, el terremoto cambió las dinámicas culturales de Castro, lo que marcó un antes y un después en muchos aspectos, tanto sociales, como territoriales y comerciales, cuyas repercusiones se extienden hasta el día de hoy:

“Mayo de 1960 representa el principio del fin de muchas cosas, aquellas propias de la vida puertas adentro, como era de algún modo, la vida anterior a la carretera, cuando el corto vecindario se conocía por sus nombres. Con el terremoto de 1960 comenzó el ocaso de los vapores, de los ‘caminos del mar’, de la ‘cultura del velamen’, y el ocaso de La Playa, aquella colorida ‘feria del mar’ que daba peculiar fisonomía a ese Castro de vocación marítima y con ello también vino el ocaso de la costanera, de calle Lillo con su antiguo rol, y de calle Blanco que tuvo que ceder ante el mayor empuje comercial de las calles interiores, como San Martín, en los años setenta” (1996, p.7).

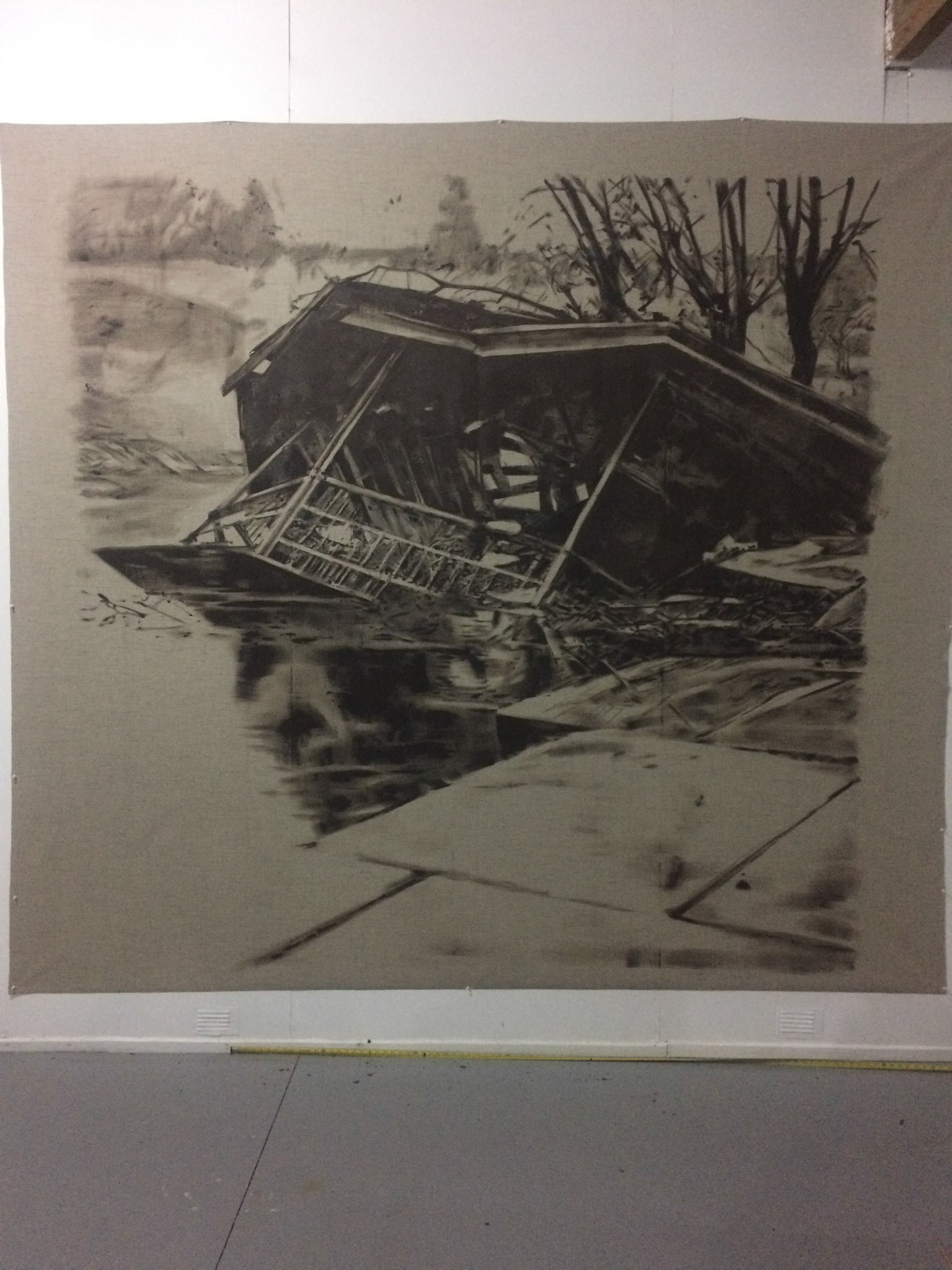

Con todo lo anterior, la pintura fue mi principal medio expresivo para abordar el fenómeno telúrico en Chiloé. Trabajé con esmalte al agua sobre tela. Dada las frías y húmedas temperaturas del MAM Chiloé, tomé la decisión de trabajar con textil black out, que tiene la particularidad de ser aislante térmico, entre otras variadas cualidades vinculadas a la luz y el sonido, lo que posibilitó que las obras no sufrieran mayores deformaciones por la temperatura y el paso del tiempo.

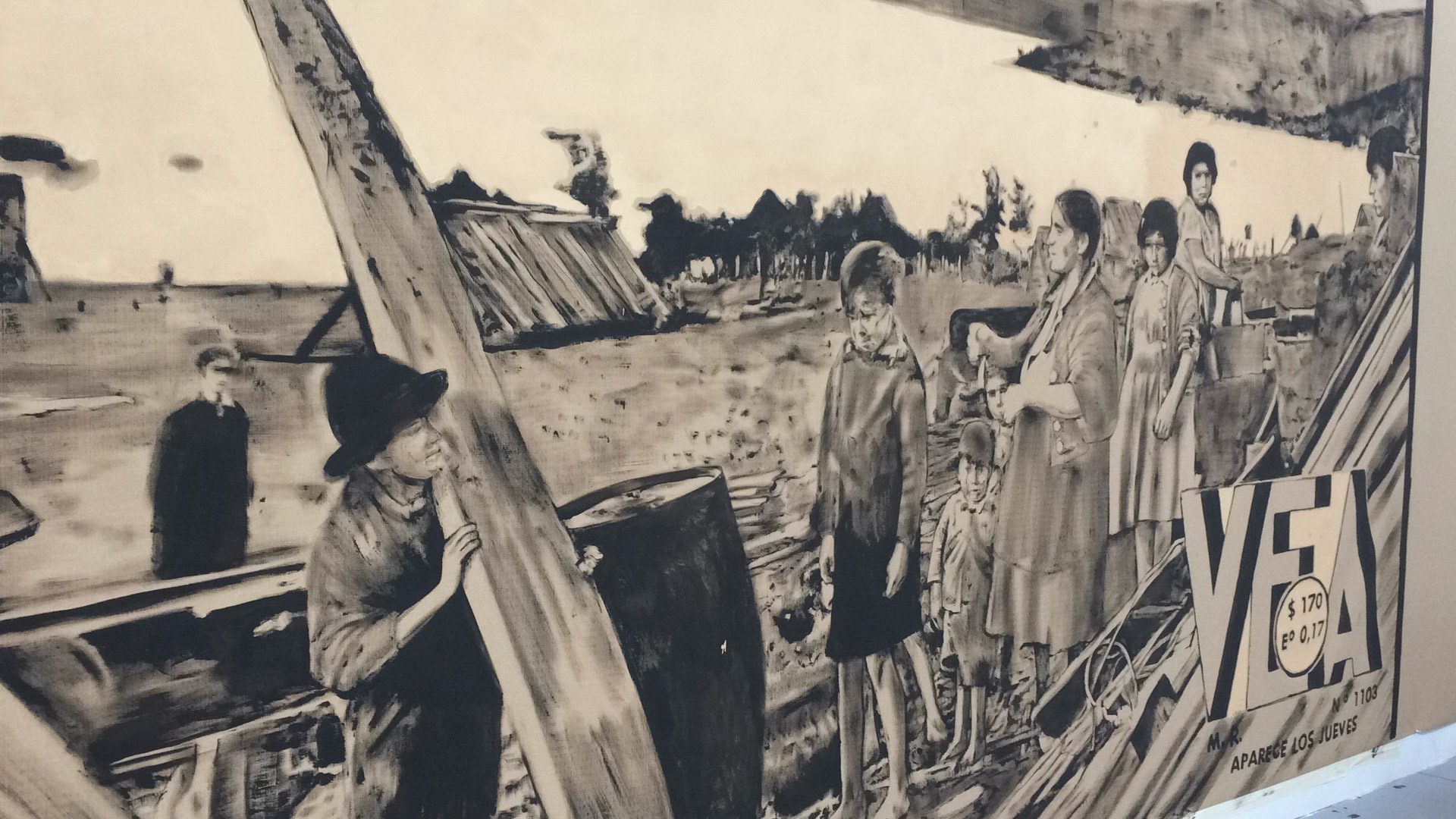

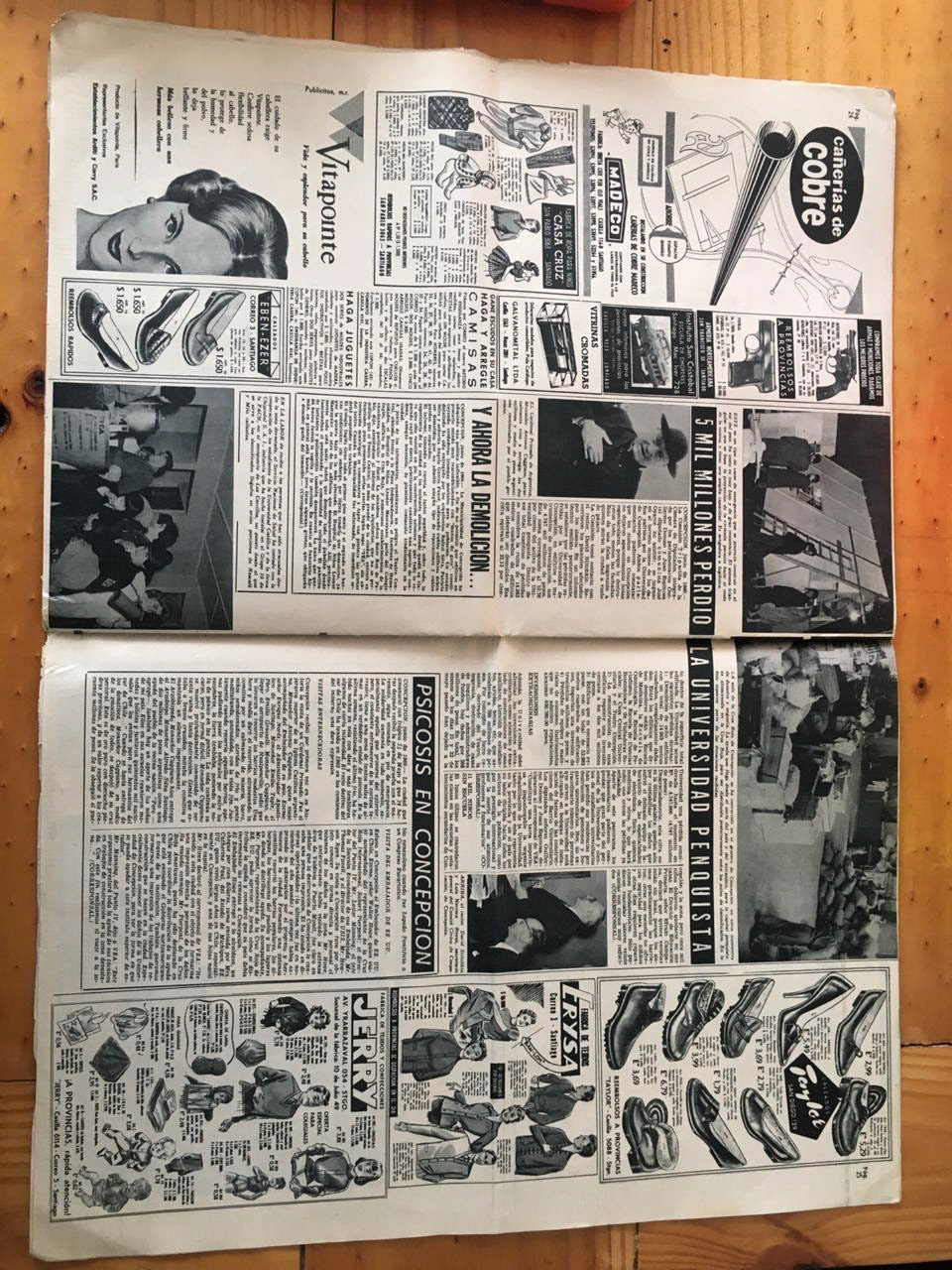

El título que aglomera el trabajo que mostré en la Exposición Regional fue Lo perdieron todo. Este es el título de la revista VEA del 16 de junio de 1960. Desde allí saqué imágenes y textos con los que luego hice las pinturas. Me interesó este nombre porque dispone, en un mismo lugar, cuestiones relevantes: un tiempo, una condición y una medida. El correlato temporal está situado en el pasado, por tanto, apela necesariamente a una revisión histórica, reconocimiento de relatos y memorias. Asimismo, da cuenta de una condición que tiene que ver con la noción de pérdida, por tanto, cuestiones vinculadas a la merma, el quebranto, el mal, la ruina y/o la muerte. Y, por último, la medida de esta pérdida que, en este caso, fue radical, extrema, drástica, apela a la totalidad. Se trata, por tanto, de un título rotundo. Al mismo tiempo, construye un misterio en torno a preguntas como: ¿Quiénes lo perdieron todo? ¿Qué fue lo que perdieron? ¿Porqué lo perdieron? ¿Es posible que aquello que motivó dichas pérdidas vuelva a ocurrir? y ¿Qué podría hacer el arte ante este drama?

Aun cuando, desde un punto de vista formal, mi investigación no haya buscado dar respuestas a estas interrogantes, estas mismas se transformaron en las vías de acceso directo hacia nuevos universos de significación y conocimiento, rutas repletas de imágenes y reflexiones profundas con repercusión directa en las obras propuestas.

Uno de los aspectos que me interesó abordar en mis pinturas fue el de la escala, exacerbando el encuentro significativo entre cuerpo e imagen. Cuando digo cuerpo, me refiero a mi propio cuerpo, así como al del espectador. En ambos casos, el cuerpo es sobrepasado por el tamaño de las piezas. Con ello incentivo el juego de las distancias, proximidades, desplazamientos, conciencias de detalles e imagen de conjunto. En este sentido, me interesó pasar de lo minúsculo a lo enorme. Las fotografías que usé para representar fueron pequeñas imágenes de prensa escrita que no superaban los diez centímetros de ancho. Cuando pensaba en dichas imágenes, se me hacía muy difícil poder mirarlas al detalle y, por tanto, sopesarlas adecuadamente. Por ello, multipliqué exponencialmente su escala. Por otro lado, el color de las obras expuestas tuvo que ver directamente con el color amarillento de las hojas de los archivos de prensa con los que trabajé. De igual modo, se vinculaban directamente con los colores de las vigas del museo –que, por cierto, fueron imposibles de eludir, pues forman parte fundamental del museo–, por ello, traté de forzar una interacción entre obras y museo.

En concreto, mostré tres pinturas que buscaron reflexionar sobre el imaginario telúrico de Chiloé. Cada imagen construida exhibió aspectos particulares del drama de la época, donde el riesgo y la vulnerabilidad fueron los factores principales de la configuración de la catástrofe. Allí, entre manchas que representan agua, barro y escombros, se divisaban niños descalzos y adultos levantando lo que se pudo salvar de las estructuras fragmentadas. Sin embargo, aun cuando trabajé muy duro, me faltaron muchas cosas por resolver, entre ellas una serie de 25 frottages de las sexagenarias ruinas del muelle de Aldachildo en la isla de Lemui.

Por último, como cierre, debo mencionar que me interesó de sobremanera trabajar al alero de esta residencia, porque me sacó de eso que he construido como rutina, tanto artística como laboral en su aspecto más tradicional. Con ello, me obligó a repensar mis hábitos y costumbres. Fue, por tanto, una oportunidad para explorar nuevos senderos o simplemente para recoger y/o poner a prueba esas ideas que quedaron postergadas entremedio de inercias y ansiedades. De este modo, fue una salida de mi zona confort, un escape total, asumiendo todos los costos y complicaciones que esto mismo luego significó. Como toda aventura, esta inmersión en lo desconocido, exigió solo lo esencial: nada de cavilaciones e inseguridades. Por ende, puse a prueba mi sensibilidad con el mayor rigor posible, tanto para valorar las particularidades de este territorio, como para apreciar las historias de las personas que lo viven, habitan y construyen.

Bibliografía:

Urbina-Burgos, Rodolfo (2013). Aspectos del vivir de los chilotes: Castro 1950-1960. Concepción: Okeldán.

Urbina Burgos, Rodolfo (1996). Castro, Castreños y Chilotes 1960 – 1990. Valparaíso: Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso de la Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

EN

Between September 1 and 30, 2019 I was in residence at the Museum of Modern Art of Chiloé (MAM Chiloé) after having been awarded the Ca.Sa. 2019 of the Ca.Sa Foundation. Along with this experience, the award included being part of the 11th MAM Chiloé Regional Exhibition from October 12 to December 12, 2019.

I had never been to Chiloé before, therefore, from the first moment I found out that I had won the award, I was very excited to get to know Castro and its surroundings. In general, it was an incredible opportunity to reflect and make art in a beautiful environment, with exuberant flora, amazing birds and an invaluable architectural heritage. However, as time progressed, the different and complex folds of their traditional culture, memories and, especially, their stories of exclusion, as well as urban and rural exploitation, were revealed to me.

In the midst of cold winds and intermittent rains, I would say that the MAM Chiloé residence was pure warmth, an environment of containment and creative protection, which awakened and captivated all my senses. This has a human team that, at all times, gave me the help and confidence I needed. Its more than 30 years of history have forged a robust and consolidated space for artistic production. Given the location of the residence, relatively far from the center of Castro, on the heights of the Municipal Park, the experience at MAM Chiloé was very similar to what could have been a spiritual retreat, away from all the noise and bustle of life. urban, which made possible the development of deep processes of reflective introspection. Such a calm that nothing foreshadowed the revolution that would soon break out in our country.

As a first approach to the residency, I thought of an exploratory work methodology, rather than a specific project to which I would be accountable. Having a fairly clear methodology allowed me to put everything in order and work with greater freedom. As a first instance, I forced myself not to bring any artistic material from my toolbox to the residence; I wanted whatever was coming out to necessarily have to do with the place. This prompted me to be more awake to new possibilities; diversify my artistic strategies; limit my creativity; and value the principle of economy in which nothing is lost and everything is transformed into an advantage for what can be built as a work. As an investigative exploration, I sought to explore the territory, paying attention, first, to its streets, passages and trails; then, jumping fences and climbing endless slopes, discovering the reminiscences of the jungle landscapes described in Darwin's logs. Similarly, I visited the main cultural centers of Castro and its surroundings, in order to see how their local representations are set up and managed. Likewise, I reviewed the general literature that accounts for the imaginaries of Chiloé and, last but not least, I put together a mental map with the different places of sale of materials of the most varied nature. With this basic structure, I began to collect the different material and symbolic elements that would define my artistic work.

The first thing I did when I arrived at the residence was to run around its surroundings, to weigh its steep slopes and, at times, hostile temperatures. I managed to travel more than fifteen kilometers around. The show that was presented to me was simply wonderful. Even though I haven't spent much of my residence time getting to know its diverse and popular corners, I was able to visit incredible towns such as Lemuy, Chonchi and Queilen. It is clear that I need to return, even more so when everyone has mentioned to me that every year the landscape changes abruptly: collapse of heritage houses, accelerated expansion of urban areas, devastation of native forests, limitations on artisanal fishing, and lack of control in around caring for the environment in general. With all of the above, the influence of the territory was a fundamental feature in my work; hence the motivation to address his telluric and tectonic imaginaries.

Among the many and varied stories that the island keeps, I focused on the way in which it was hit by the earthquake of May 22, 1960, one of the largest recorded in the history of mankind. According to Professor Rodolfo Urbina Burgos, historian specializing in Chilote issues, the 1960 earthquake:

“…it left some 500 brown families homeless, either because their houses were uninhabitable due to the damage suffered, or because they were tilted due to the unevenness of the land, especially on the slopes, which was where it moved the most, or because they were flooded, as in the whole palafitte cordon, already entirely destroyed by the earthquake and the fires, as in Blanco and Thompson streets” (1996, p.40).

Although this seismic event has been known worldwide as the Valdivia earthquake, less known is that Chiloé suffered as many misadventures and hardships as Valdivia itself. Apart from the earth movement and subsequent tsunami, immense fires with great destructive power occurred in Chiloé. Urbina explains that:

“In Castro the tide was rising quickly, but gently, as if a pond were being filled. Submerged were all the sectors of the shore: Pedro Montt, Aguirre Cerda, Barrio Gamboa and Calle Lillo. Many of the coastal houses detached from their piles sailed through the bay at the whim of the currents. The sea took some fifty houses, says the geographer Pedro Cunill. Similar scenes of floating houses were seen in Ancud” (2013, p.220).

Also, given the big move:

“Inside the houses nothing could be kept standing. Furniture, shelves, wardrobes, forks fell; crockery and glass were shattered; heavy appliances, tables and beds were displaced, and stairs fell or became dislodged. Everything was overturned, confused or destroyed. The wood-burning stoves were turned over and the braziers lit at after-meal time, as was the custom on a winter Sunday when the family gathered around the fire. Then the fires started. These began to sprout on Thompson Street, above, and on Irarrázaval, below, to prepare for Blanco, which was caught by fire from both ends” (2013, p.218).

However, in order to learn firsthand about the memories surrounding this event and its consequences on local imaginaries, it was important not only to consult its official literature, but also to listen directly to the stories of those who suffered the earthquake and who are still alive to tell about it. To do this, I made an open call with the aim of knowing these stories, this in collaboration with the Castro Creation Center (CECREA). The call went as follows:

“Do you know of anyone who experienced the earthquake of May 22, 1960 here in Chiloé? Invite him to share his story at the CECREA in Castro on Thursday, September 26. Together we will build an emotional repository of the telluric memory of the island. If your story is accompanied by photographs and/or press clippings, these can be digitized and shared later”.

Although I was able to carry out the collection activity, due to lack of time I could not systematize the information collected. However, in one way or another, all the stories revealed a deep existential anguish, in which resignation and abandonment filled the visions of the drama. For example, Patricia Gerding Knopke, director of the Luis Segovia Ross School, found among the things of her recently deceased mother, Laura Knopke Rutherford, a manuscript that gave an account of the disaster in the following way: “When I started to climb the Baquedano slope I found to my husband, who after the fires were put out heard that the sea was rising and thought as I did, that the family should be united and perhaps all die together”. Even though, for reasons of time and thoughtful prudence, I could not account for this type of narrative in the exhibition, I wanted the images to be able to express something of this type of story.

According to Professor Urbina, the earthquake changed the cultural dynamics of Castro, which marked a before and after in many aspects, both social, territorial and commercial, whose repercussions extend to the present day:

“May 1960 represents the beginning of the end of many things, those of life indoors, as it was somehow, life before the highway, when the short neighborhood was known by its names. With the 1960 earthquake began the decline of the steamboats, of the 'roads of the sea', of the 'culture of sailing', and the decline of La Playa, that colorful 'fair of the sea' that gave a peculiar physiognomy to that Castro of maritime vocation and with it also came the decline of the waterfront, Lillo Street with its old role, and Blanco Street that had to give in to the greater commercial thrust of the interior streets, such as San Martín, in the seventies” (1996 , p.7).

With all of the above, painting was my main expressive means to approach the telluric phenomenon in Chiloé. I worked with water enamel on canvas. Given the cold and humid temperatures of the MAM Chiloé, I made the decision to work with black out textiles, which have the particularity of being thermal insulators, among other qualities linked to light and sound, which made it possible for the works not to suffer major damage. deformations due to temperature and the passage of time.

The title that brings together the work that I showed at the Regional Exhibition was They Lost Everything. This is the title of the magazine VEA of June 16, 1960. From there I took images and texts with which I later made the paintings. I was interested in this name because it has, in the same place, relevant questions: a time, a condition and a measure. The temporal correlate is located in the past, therefore, it necessarily appeals to a historical review, recognition of stories and memories. Likewise, it accounts for a condition that has to do with the notion of loss, therefore, issues related to decline, loss, evil, ruin and/or death. And finally, the extent of this loss, which in this case was radical, extreme, drastic, appeals to the whole. It is, therefore, a resounding title. At the same time, build a mystery around questions like: Who lost everything? What was it that they lost? Why did they lose it? Is it possible that what caused these losses will happen again? And what could art do in the face of this drama?

Even though, from a formal point of view, my research has not sought to provide answers to these questions, they have become direct access routes to new universes of meaning and knowledge, routes full of images and profound reflections with direct repercussions on the proposed works.

One of the aspects that I was interested in addressing in my paintings was that of scale, exacerbating the significant encounter between body and image. When I say body, I mean my own body as well as that of the viewer. In both cases, the body is exceeded by the size of the pieces. With this, I encourage the game of distances, proximities, displacements, awareness of details and overall image. In this sense, I was interested in going from the tiny to the huge. The photographs I used to represent were small print media images no larger than four inches wide. When I thought about these images, it was very difficult for me to look at them in detail and, therefore, weigh them properly. Therefore, I exponentially multiplied its scale. On the other hand, the color of the exhibited works had to do directly with the yellowish color of the pages of the press archives with which I worked. In the same way, they were directly linked to the colors of the museum's beams – which, by the way, were impossible to avoid, since they form a fundamental part of the museum –, therefore, I tried to force an interaction between the works and the museum.

Specifically, I showed three paintings that sought to reflect on the telluric imaginary of Chiloé. Each constructed image exhibited particular aspects of the drama of the time, where risk and vulnerability were the main factors in the configuration of the catastrophe. There, among stains that represent water, mud and debris, barefoot children and adults could be seen lifting what could be saved from the fragmented structures. However, even though I worked very hard, I still had many things to solve, including a series of 25 frottages of the sixty-year-old ruins of the Aldachildo wharf on the island of Lemui.

Finally, as a closing, I must mention that I was extremely interested in working under the wing of this residence, because it took me out of what I have built as a routine, both artistic and work in its most traditional aspect. With this, it forced me to rethink my habits and customs. It was, therefore, an opportunity to explore new paths or simply to collect and/or test those ideas that had been postponed between inertia and anxieties. In this way, it was a departure from my comfort zone, a total escape, assuming all the costs and complications that this later meant. Like any adventure, this immersion in the unknown required only the essentials: no musings and insecurities. Therefore, I tested my sensitivity as rigorously as possible, both to value the particularities of this territory, and to appreciate the stories of the people who live, inhabit and build it.

Bibliography:

Urbina-Burgos, Rodolfo (2013). Aspectos del vivir de los chilotes: Castro 1950-1960. Concepción: Okeldán.

Urbina Burgos, Rodolfo (1996). Castro, Castreños y Chilotes 1960 – 1990. Valparaíso: Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso de la Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

Proceso de trabajo